Abstract

We study the extent to which French entrepreneurs mobilized in an online collective action against the generalization of the health-pass policy in summer 2021. We document the dynamics of registrations on the website Animap.fr where entrepreneurs could claim they would not check the health-pass of their clients. We first note an over-representation of complementary and alternative medicine practitioners among the mobilized people. We also suggest that professionals related to the touristic industry mobilized on the website. Second, we show that the government announcements led to an increase in the mobilization. However, they did not affect the diversity of the entrepreneurs joining the action. This lack of diversity may have restricted the pool of potential participants as well as limited the identification of the “public opinion” to the mobilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In July 2021, E. Macron the French Président de la République announced the expansion of the health-pass (“pass sanitaire”) policy.Footnote 1 The document became mandatory in order to access many places such as restaurants, sports facilities, shops in large malls, or to travel between regions by the public transportation system.

While this new policy boosted the vaccination campaign, it also generated a series of protests that gathered between 150,000 and 250,000 demonstrators weekly. On top of those demonstrations, some small businesses decided not to enforce the law. As far as we know, there exist no official statistics on the number of controls and the percentage of recalcitrants. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that—while the policy was generally enforced—the health pass of clients was not always checked by professionals.Footnote 2 Few small business owners also claimed on social media or the internet that they would not enforce such a health-pass policy. In particular, the website Animap.fr created a directory for businesses that claimed they would not ask for the health pass of their clients. According to the website, more than 7,400 professionals registered.Footnote 3

Who are those professionals? How did they react to E. Macron’s speech? Did the speech enlarge the pool of protesters? As the vaccination against COVID-19 became a pillar of the public policies seeking to fight the pandemic, those questions are crucial. Indeed, the health-pass policy builds incentives schemes that push people to get vaccinated (people need the document to keep doing some recreational activities), however as controls are realized by the professionals themselves, their participation is crucial in the success of the vaccination policy. Moreover, those professionals may have conflicting incentives: enforcing the health-pass policy implies that professionals could impede potential customers from accessing their facilities.

We investigate those questions using the registrations on the website Animap.fr. While it is one among the many websites where opponents to the health-pass policy discussed and organized, Animap.fr has the advantage to target professionals directly, to emphasize a single action (refusing to ask the health-pass of clients), and to have received some media coverage.Footnote 4 As such, the website allows us to study a mobilization by anti health-pass professionals.

We first document the types of professionals registered on the website and underline the critical presence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners. This is all the more interesting because the policy did not target CAM professionals who were not required to check the health-pass of their clients. This observation is however consistent with the long-noticed fact that CAM professionals are pillars of the anti-vaccination movements (as already remarked in Kaufman, 1967). Although they form the more numerous group, Animap.fr does not only gather CAM practitioners. We suggest that tourism may also have been an important mobilizing dimension as we find more registrants in départements that benefit from a developed touristic industry.Footnote 5 The share of professionals directly targeted by the measure is also (weakly) correlated to tourism.

Then, we turn to the study of the announcement of the generalization of the pass. We show that the number of registrations peaked in the days that followed E. Macron’s speech (we measure approximately 170 additional registrations per day during the first week and 66-71 additional registrations during the second one). However, the effect was short-lived and we observe little effect after two weeks.

Despite this intensification of the movement, we show that the announcement and the subsequent street protests had negligible effects on the profiles of professionals registered on the website. While heterogeneous, they lacked diversity from the start and failed to attract people from other industries. Indeed, we observe no change in the likelihood that professionals work in the CAM industry. Similarly, we observe no change in the likelihood that professionals belong to the categories likely concerned by the policy. Those results are confirmed by another methodology—based on cosine similarity—that seeks to detect whether there is a global change (i.e. looking simultaneously at all categories) in the profiles of registrants.

The previous finding may explain the relative (apparent) failure of the mobilization.Footnote 6 The number and the diversity of people participating to a protest are important dimensions to its success (see: Tilly, 2004, Tilly and Tarrow, 2015, Wouters and Walgrave, 2017, Wouters, 2018). Diversity implies that a movement managed to recruit members in several groups and thus could potentially benefit from a large pool of other recruits. Moreover, diversity facilitates the identification of public opinion with the movement. Here, we show that the movement was not diverse to begin with and that it failed to diversify after the announcements of E. Macron.

Along similar lines and although this requires being cautious, our observations might also explain why the rebound in the movement in January 2022 (due to the transformation of the health-pass into a vaccine-pass) gathered fewer protesters (around 100,000 people on the 8th of January and then half as many the following weekend). Professionals from the touristic industry likely have demobilized as the summer touristic season ended. In such a case, the social base of the movement would had been even more reduced.

Moreover, our findings have policy relevance: (a) it documents the type of professionals that may be reluctant to the health-pass policy. (b) It suggests that there might coexist several motives behind such a mobilization: on top of ideological motives, some professionals may have more direct economic incentives. (c) Finally, it suggests that despite the (large) number of protesters, the mobilization remained limited to specific groups and failed to diversify.

The article is organized as follow. In Sect. 2, we review the literature and underline our main contributions. In Sect. 3, we provide information on the health-pass policy and anti health-pass mobilizations. In Sect. 4, we detail our data and we display descriptive elements on the entrepreneurs that registered on the website Animap.fr. In Sect. 5, we study the effect of the generalization of the health-pass. In particular, we wonder whether the people that registered after the 12th of July resemble the first registrants. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes.

Literature and main contributions

This article speaks to three strands of the literature: on protests and mobilization against policies, on the relationships between complementary and alternative medicine and vaccination and finally, on the policies implemented during the pandemic. We discuss each literature separately.

Protests, diversity, heterogeneity and reactions to governmental announcements

The literature on protests, social movements and contentious politics—as connected to the one on collective actions—has discussed the effect of heterogeneity (or diversity) of participants on their successes. Authors generally pinpoint the fact that an heterogeneous group could lack trust. In turn, this could impede collective actions. On the contrary, heterogeneous groups may have access to more diversified resources than homogeneous ones, which could be necessary for the success of actions. Similarly, the heterogeneity of groups may help solve the free-rider problem as individuals with more stakes could contribute to the action whatever the behavior of others. In turn, this may re-insure the other members of the group.Footnote 7 Regarding protests more specifically, as (intuitively) suggested by Charles Tilly’s WUNC model (WUNC stands for worthiness, unity, number and commitment Tilly, 2004,Tilly and Tarrow, 2015)—and further tested by Wouters and Walgrave (2017)—the number of protesters is a critical criteria for politicians to react to protests.Footnote 8 This calls for attracting people from several groups into the protests in order to mobilize as many persons as possible. Wouters (2018) also adds the diversity dimension to the initial WUNC framework. Through an experiment, he shows that diversity of movements make it more appealing for the general public as more people can identify with the movement.

Scholars also discuss the fact that events serve as a signal during protests and social mobilizations. For instance, Sangnier and Zylberberg (2017) showed that after protests in Africa, people update their belief about the government, often leading to a decrease in trust (in the government and institutions).Footnote 9 Government announcements (and policies) may also affect the emotions of individuals and their perceived fairness of public policies. In turn, this could led them to mobilize.Footnote 10

Our work considers these two branches of the literature on protests. We study the extent to which announcements of a government (the extension of the health-pass) affected both the number and the diversity of participants involved in a mobilization against the health-pass policy. We show that although the number of participants increased, their diversity was unaffected.

CAM and vaccination

The role of CAM professionals in anti-vaccination movements has long been noticed. For instance, naturopaths and homeopaths were leading figures of the nascent US anti-vaccine movement during the nineteenth century (Kaufman, 1967).

That said, the exact relationship between CAM and hesitations toward vaccines is far from clear. If some studies found a correlation between non-compliance toward vaccination and obtaining information from alternative health practitioners (Chow et al., 2017),Footnote 11 several studies cast doubt on the causality of the relationship or its strength (Attwell et al., 2018; Bryden et al., 2018; Hornsey et al., 2020). For instance, Hornsey et al. (2020) suggest that trust in CAM plays a role but that it remains modest; distrust in conventional medicine being more influential in vaccine hesitancy. This distrust in conventional medicine also appears in the interviews of CAM users realized by Attwell et al. (2018). Other studies such as Deml et al. (2019), show that CAM themselves do not always have anti-vaccine attitudes. Among the 17 professionals they interviewed, only two had clear anti-vaccine positions. Maybe, rather than an opposition to vaccines, CAM professionals emphasize a rhetoric of “individual choice” (Deml et al., 2019).

Our work does not contradict those previous results; it nuances them. We pinpoint the massive presence of alternative medicine practitioners among those who registered on Animap.fr. Thus, our study clearly shows that CAM practitioners were crucial actors in the mobilization against the health-pass. It recalls that many CAM practitioners do not hesitate to mobilize against incentives schemes in favor of vaccines. They could influence attitudes toward vaccination through contentious politics and collective actions (and not necessarily through direct interactions with patients).

Public policies during the COVID-19 pandemic

Finally, this paper also brings to the growing literature that studies the policies enacted during the pandemic and the reactions to those policies. Regarding the vaccination in general, Blondel et al. (2021) discuss why people could refuse to get vaccinated against COVID-19. They suggest that “rational” actors should accept the vaccine and therefore, cognitive behavioral biases must be mobilized to explain vaccine hesitancy. Regarding the compliance to the policy implemented during the pandemic (such as lock-downs), Bargain and Aminjonov (2020) point out that non-compliance is mostly explained by a lack of trust in the government.

We are aware of only two studies directly dedicated to the French health-pass policy. Oliu-Barton et al. (2022) suggest that the policy was highly effective. According to the authors, the vaccine certificate increased vaccine uptake by 13% points. It therefore avoided 32,000 hospitalizations and 4,000 deaths and a decrease in GDP of approximately six billion euros (because the policy avoided further lock-downs). Ward et al. (2022) slightly nuances the finding. While they underline the success of the measure in terms of vaccination rates (below, we also present a graph on the effect on the vaccination rate), they also suggest that the pass did not affect hesitancy itself. Moreover, they suggest that the incentives schemes created by the pass had less effect on the elderly, the group who faced the highest risks of serious illness.

We also analyze the effect of the health-pass policy but focus on anti pass mobilizations. Actually, and although we discuss anti-pass movements (and not refusal of the vaccination), we see our work as complementary to Blondel et al. (2021). While they highlight the role of behavioral biases, we highlight the fact that ideological motivations (for instance, for CAM practitioners) and economic incentives (related to tourism) may help explaining the anti-pass movement. Thus, behavioral biases interact with beliefs, preferences and incentives.Footnote 12

More generally, as we underline the heterogeneity among professionals who refuse to apply the health-pass policy, we show that this movement resembles the other protests against the policies implemented during the pandemic. Kowalewski (2021) or Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2021) already pinpointed the fact that protesters had highly heterogeneous (religious, ideological or economical) motives when they opposed lock-downs. This heterogeneity is also discussed in Martin and Vanderslott (2022) who suggest that contests against COVID-19 health policy brought together pre-existing anti-vaccine groups and newly form groups interested (only) in COVID-19 health measures. Among those groups, the motivations could also vary from mere discomfort (especially against mask wearing), worry about the side effects of vaccines, to ideological opposition to imposition on freedom or or beliefs in conspiracy theory.

The background

We use the expansion of the health-pass in France in order to study the reactions of opponents to such policy and their online behavior. We now describe the context of the policy.

Health-pass and governmental decisions

The health-pass is a document that attests either that (a) an individual has been tested negative to the COVID-19 or that (b) she is somehow protected against the disease. This could be the case because an individual developed an immunity due to a previous contamination or got vaccinated.Footnote 13

The health-pass has been implemented in France in May 2021. It was initially required only for a very limited number of events that gathered more than one thousand people, such as concerts or large public meetings. Interestingly, during the first parliamentary debates (in May, 2021), députés claimed that the health-pass would not be generalized and would be required only in those few cases.Footnote 14

Nevertheless, on the 12th of July, after several days of consultations of medical authorities and discussions with political leaders, E. Macron announced that—due to the worsening of the pandemic situation (because of the delta variant)—the pass would become mandatory in many more places, such as restaurants or to travel through trains and airplanes between regions.Footnote 15 A brief legislative debate followed this declaration: the lower chamber (the Assemblée Nationale) voted the law on the 23rd of July and the upper chamber (the Sénat) on the 25th of July. The law was then examined and approved by the Conseil Constitutionel on the 5th of August (the highest French judicial authority). Finally, the pass became mandatory on the 9th of August even though part of the expansion was already applied (since the 21st of July).

As a matter of public health, the policy was a success. The number of first doses of vaccine delivered by week jumped to more than 2.5 million after the speech of E. Macron while it had felt below 1.5 million at the end of June (see left graph in Fig. 1). As mentioned above, Oliu-Barton et al. (2022) find that the health-pass has prevented 4,000 deaths in France through the direct protection provided by vaccines.

Protests against the Health Pass

We can also observe skeptical or anxious reactions after the announcement of the generalization of the pass. For instance, there was an increase in the number of internet searches on the side effects of vaccination (see the right graph in Fig. 1).

Use of vaccines and internet researches on side effects of vaccinations. Source: The data were obtained from www.GoogleTrend.com on September 9, 2021. The left graph shows the use of the first COVID-19 vaccination dose during the summer of 2021 and the right graph shows the relative searches (the number of searches relative to the maximum number of searches) on Google in France on the “side effects” of vaccination. Notes: The two dashed lines respectively correspond to the speech of E. Macron on the 12th of July and when the expansion officially became effective on the 9th of August

The generalization of the pass also triggered reactions of both so-called “anti-vacc” (against vaccination) and “anti-pass” (against the health-pass) groups. It must be noted that the two movements do not necessarily overlap in theory. The anti-vaccination movement struggle against vaccination (or the one against COVID-19) for various reasons (individual liberty, safety of vaccines, etc.).Footnote 16 The health-pass policy creates an incentive scheme that pushes people to get vaccinated. As such, it gathered opposition from people who refused the restrictions to the liberty of non-vaccinated people. In many instances though the two movements are hard to distinguish as “anti-pass” groups may use “anti-vaccination” arguments and both groups emphasize individual liberty. The blurred border between anti-pass and anti-vacc sometimes appears for people registered on the website Animap.fr that we consider below.Footnote 17

The action of both groups mostly consisted of protests organized every Saturday. Those protests were either self-organized or organized by groups close to (often far right) politicians. Demonstrators used various websites (Animap.fr, Reinfocovid.fr,Tousantipass.fr)Footnote 18 and social media (all the previous websites seem to have Facebook, Twitter, Tik Tok or Telegram accounts) in order to transmit—sometimes dubious—information about the vaccines, the health-pass policy or merely to explain where and when to protest.

As shown in Fig. 2, protests gathered more than 150,000 persons every weeks in July and August, with a peak above 237,000 demonstrators on the 7th of August.Footnote 19 Figure 2 also reveals the online searches associated with the keyword “protest” between the beginning of July and the 9th of September. While they were virtually no search before the speech of E. Macron, we then observe peaks every Saturday. This may correspond to two phenomena: (a) people that seek to obtain information on where to protest and (b) people that wanted to learn ex post the number of demonstrators.

Timing of the protests. Source and notes: The graph shows the number of demonstrators (left axis). The number was obtained from newspapers. We report the estimation of the Police (demonstrators reported higher numbers). The relative searches for the keyword “protest” on Google in France (right axis) was obtained from www.GoogleTrend.com on the 9th of September 2021. It corresponds to the relative number of searches (the number of searches relative to the maximum number of searches). The two vertical dashed lines respectively correspond to the speech of E. Macron on the 12th of July and the expansion of the pass policy on 9th of August

Animap.fr

Among the websites used by the anti-pass mobilization, we focus on Animap.fr. The website allows professionals to register if they commit not asking their clients whether they have a valid health pass (registration is free). In such a case, each firm can create an online page with a brief description and contact details (mail, address, etc.). According to the website, approximately 7,400 professionals had registered in January 2022.Footnote 20 Entrepreneurs seem to used those pages as a tool to advertise their firms.

As far as we know, the website does not check whether professionals control or not the health pass of their clients. Moreover (as we discuss below), the majority of the professionals registered seems not to be concerned by the obligation to request a health-pass from its customers. This is however not true for all firms and, for instance, there are restaurants among the firms. However, we find neither large companies (such as cinemas) nor chain stores. The registrations, therefore, seem to concern small businesses and self-employed individuals mainly.

We consider that registering on the website signals a strong anti-pass position. This could be positive for firms (if it attracts client) or costly because the firm may lose clients (who are pro-pass) or because it can expose firms to legal problems. Although we ignore whether it was the case, the registration on the website could increase the probability that the company will be confronted with a control by the authorities, a fortiori, of being sanctioned.Footnote 21

History of the website—animap.fr. Source and notes: The graphs show the number of registration per day on Animap.fr (left axis). See the data section. The right axis provides the relative number of searches for the keyword “animap” on Google in France (right axis) that we obtained from www.GoogleTrend.com. It corresponds to the number of searches with respect to its maximum. The two vertical dashed lines respectively correspond to the speech of E. Macron on the 12th of July and the extension of the pass on the 9th of August

The history of the website is linked to the anti health-pass mobilization. Using an online search for the keyword “animap” and the registrations on the website, Fig. 3 shows that the website did not exist before May, 2021. After an intense activity in May, it reduced in June, before a huge increase following the announcements of E. Macron on the 12th of July when both researches on Google and registrations per day peaked. We also observe a smaller surge in online searches when the health-pass was officially enacted. However, this was followed only by a minor increase in registrations that seems significantly lower compared to the previous waves.

Data and descriptive statistics on registrations

Source

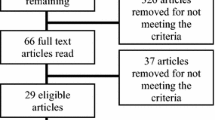

Our primary source of data is the website Animap.fr. We used web scrapping techniques in order to recover the pages created by firms between the 16th of April and the 8th of September 2021.Footnote 22

We did not collect personal information from registrants. We focus and recover the following elements: (a) the name of the firms, (b) the cities where they are active, (c) the category of firms, (d) the description of the firms written by the professionals (if any) and finally (e) the date when the pages have been created. Regarding the categories of professionals, Animap.fr created its own classification that contains 19 possibilities. We primarily use this categorization as often, we were not able to mach firms to categories provided by other taxonomies.

Animap.fr: the categories of professional

We first investigate the categories of professional that registered on the website. Here, we use the profiles of 6,676 professionals that created a webpage on Animap.fr in metropolitan France.

In Fig. 4, we display the percentage of professional by categories (using the categories offered by the website). As one can see, 22.5% of professionals are related to the health industry. Among them, the vast majority of those professionals are related to the CAM sector (naturopaths, homeopaths, people providing energetic health care, etc.).

The previous percentage appears to be underestimated. Using the descriptions (available for 35.11% of firms), we find that 21.7% of the firms that did not register in the “health and medicine” category can be related to CAM practitioners. They often selected the category “other” or “service.”

This observation—the massive presence of CAM—has policy relevance. We already mentioned the critical role played by complementary and alternative medicine practitioners in the history of the anti-vaccination movements (Kaufman, 1967). If scholars doubt that those professionals have a causal influence on vaccine hesitancy (Bryden et al., 2018) or that the growth of “anti-vaccine” movement explains decreasing trend in vaccination (Blume, 2006), we pinpoint that CAM professionals play a leading role on Animap.fr. Thus, they appear to be strongly mobilized against a policy that encourages vaccination. This recalls that attitude toward vaccinations are not (only) built through direct interactions between patients and health care providers. Those providers also engage in collective actions and contentious politics.

That said and although CAM professionals appear to form the largest group, this does not mean they are the sole. For instance, we find 3.76% of the professionals in the “gastronomy” industry (often, they are restaurateurs). Those professionals were targeted by the policy and had to check the passes of their clients. Similarly, if we add professionals from the categories that might be directly targeted (such as, “gastronomy”, “sport and leisure”, “travel and tourism” or “art and culture”) we obtain approximately 17% of the registrants. Given that many of the professionals that faced a direct cost due to the policy may also have selected the loosely defined categories “services” and “others”, we also observe a large group of professionals that could have economical reasons to oppose the pass. Registrations on Animap.fr therefore seems to corroborate the observation by Kowalewski (2021): protesters had multiple motives to oppose the policy (economical, ideological, religious, etc.).

The geographical variation in mobilization

We now provide descriptive elements on the registrations on Animap.fr. As Fig. 3 already describes the dynamics of registrations, we focus on its geographical variation. The Fig. 5 depicts the number of registrations per département. It appears that départements near the Atlantic ocean as well as those near the Mediterranean sea had numerous registrations.

Registrations per départements. Source and notes: The map shows the number of registrations on Animap.fr per département. The data were obtained using web scrapping techniques. Our treatment. Remark: we only had data for the entire Corse (and not for the two départements). On this map, we considered that each départements in Corse had half of the registrations

We further explore this geographic variation by employing cross-sectional regressions between the number of registrations and several characteristics of the départements (such as their population census, their unemployment rates and their standard of living).Footnote 23 In particular, we investigate the correlation between the importance of the touristic industry—measured by the number of nights people spent in touristic facilities in 2019—and the number of registrations. The results of such an exercise can be observed in the first two columns of table 1. The variable that captures the touristic activity of a département appears to out-weights all other factors in column (1). Column (2) shows that it remains the case even if we control for whether the départements is a coastal one and whether it belongs to the Parisian region. These two variables actually reinforce our interpretation that seasonal tourism drive our results. While it is an important touristic area, the Parisian region is associated to less registrations. Similarly, we find even more registrations in coastal départements that might be especially concerned by the summer touristic season.

The column (3) and (4) repeat the same regression but now use the share of professionals in the health industry or the share of professionals that were likely directly affected by the policy (“Gastronomy”, “art and culture”, “travel and tourism” and “sports and leisure”). In those columns, it appears that (a) the share of professionals related to the health industry reacted little to tourism while. To the contrary, (b) the effect of tourism is statistically significant on the share of (likelly) concerned professionals.Footnote 24 We consider the regression as preliminary and indirect evidence that the logics of mobilization between the two groups of professionals differ. While the CAM (and other professionals in the health industry) were primarily mobilized on ideological reasons, other professionals may have faced mixed incentives, especially both ideological and economical ones.

Although we do not claim that the correlation between tourism and registrations on Animap.fr is causal, we believe this result must be highlighted. The fact that the touristic industry has been severely impacted by the pandemic has been widely documented.Footnote 25 The touristic industry, therefore, received some scholarly attention but existing studies focused on strategies to get through the crisis (see for instance: Bulchand-Gidumal, 2022, Li et al., 2022). To the best of our knowledge, the link between the touristic industry and resistance to health-pass policy has not been discussed.

We therefore observe an heterogeneity in the profiles of registrants. According to us, some of them mostly have ideological motives while others have both ideological and economical ones. Could this heterogeneity have undermined the mobilizations? For instance, because professionals had different claims or political objectives. Based on the few (28) firm’s descriptions that contain the words “pass” or “vaccine,” it appears that both CAM and other professionals often highlight “pro-choice” arguments. Among those professionals, those with the most extreme positions (for instance, that associate the vaccination to a crime against humanity or the pro vaccination individuals to a “Mafia”) were both health care providers or other types of professionals (and even if those few professionals could not be related to the touristic industry).Footnote 26 Therefore, if we suggest the differences in motivations between categories of professionals, we cannot conclude from our data that this led to a strong cleavage within the mobilization.

The expansion of the health-pass and the mobilization

We now study the effect of the announcements of E. Macron on the 12th of July.Footnote 27 We proceed in two steps. First, we provide estimates of the effect of those announcements on the number of registrations. Second, we analyze whether the new registrations resemble the early ones.

The effect of the announcement on the number of registrants

Method

As a starting point, we measure the extent to which the expansion of the health-pass policy on the 12th of July increased the number of registrations per day. In order to do so, we employ the following regression:

where d indicates the day and m the month. “\(\text {Registration}_{dm}\)” is therefore the number of registrations on the website during a particular day of a given month. \(\alpha _m\) is a set of month dummy variables and “\(\text {WeekPost}_{w}\)” are four dummy variables that capture weeks after the announcement. X is a vector of variables that seek to capture the dynamics of registrations. It consists in two elements: (a) a fifth order polynomial of days (normalized at the value 0 on the 12th of July), (b) day of weeks dummy variables. Finally, given the temporal nature of our data, we allow for autocorrelation in the error term \(\epsilon _{dm}\).

The intuition of the previous regression is the following. In Fig. 3, it appears that the effect of the announcement was likely positive and decreased over time. We therefore allowed for a different effect of the announcements for four weeks. Then, we measure those effects considering that there could be other (unobserved) factors that explain the dynamic of the registrations on the website. We approximate this dynamic with the polynomial, the month effects and the day of the week effect.Footnote 28

Results

Table 2 provides the results of the above regression. In column (1), we consider the four variables that capture the effect of the announcements, in column (2) we add the fifth order polynomial, then we also added the day of week dummies in column (3) and the month fixed effects in column (4).

It appears in Table 2 that the effect of the announcements disappears after 2 or 3 weeks. Moreover, the effect is more than halved between the first and the second week. It is again divided by three between the second and the third weeks. Whatever the strength of the reaction to E. Macron’s speeches, it is hardly perceived by the end of July. This being said, the table confirms the intuition of Fig. 3 and we detect a huge increase in the number of registrations after the announcement of the expansion of the health pass policy. We observe between 146 and 173 additional registrations per day during the first week after the announcement. Similarly, we find an increase in the number of registrations per day that lies in 48 and 71 for the second week. For the third week, we estimate approximately 20 additional registrations per day and finally, less than 10 for the fourth one.

Although intuitive, the previous results support the literature suggesting that events (such as demonstrations or government announcements) serve as signals and lead people to revise their beliefs (Sangnier & Zylberberg, 2017; Passarelli & Tabellini, 2017). Here, we observe a clear increase in the number of registrations after E. Macron’s speech while the expansion of the health-pass policy had already been discussed for several days by politicians and the medias. For example, we found statements by French Prime Minister J. Castex that the government was thinking about “possibly taking more coercive measures.” Similarly, Health Minister O. Veran said that vaccination “provides 100 percent protection against lockdown.” The government also consulted members of the National Assembly for advice on expanding the scope of the health passport.Footnote 29

Do we observe a diversification in the profiles?

Although it provides us with estimates, the previous analysis mostly confirms what Fig. 3 already suggested: the expansion of the health-pass policy motivated people to mobilize against health-pass and to register on Animap.fr. We now analyze the profile of registrants. More precisely, we study whether the new registrants (after E. Macron’s speech) resembles those that mobilized since May, 2021.

As mentioned in the introduction, the diversity of protesters matters at two different levels. On the one hand, the diversity of a mobilization allows the public opinion to identify with the movement (Wouters, 2018). On the other hand, in order to influence representatives, the number of participants is crucial (see Tilly, 2004, Tilly and Tarrow, 2015, Wouters and Walgrave, 2017). In turn, the number depends on the capacity to recruit people from different groups.

A first method

Answering such a question, however, raises a difficulty: we observe few of the characteristics of registrants except the “industry” and—if any—the descriptions of firms. Here, we focus on the self-declared industry. Using those categories, we can obtain a first (partial) idea on whether the expansion of the health-pass policy led to a diversification in the profiles. We employ the following analysis:

where “\(\text {Type}_{gid}\)” is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if individual i that registered on day d is of type g. Now, the variable X only contains a third order polynomial and the day of the week effects. “WeekPost” is defined as previously and capture the four weeks after the announcements of E. Macron.

In the analysis, we primarily consider two possible types. First, we look at whether the professional works in the health industry (as CAM professional with a high probability). Second, we consider whether the professional was likely concerned by the measure (because he selected one of the categories “gastronomy”, “sport and leisure”, “travel and tourism” or “art and culture”). We consider that the first type is archetypal of professionals who (a) were not directly targeted by the policy and (b) may nonetheless have ideological reasons to oppose the health-pass. On the contrary, the second category may had to check the health-pass of their clients and therefore faced direct economic costs due to the measure.Footnote 30

Finally, it should be noted that the above model is a linear probability one. Thus, the regression measures the changes in the likelihood that a professional belongs to the selected categories. In what follows, we also control our results using a logistic model. Moreover, in the appendix (Table 8), we also check that the findings are not driven by our definitions or selections of categories.

Results: LPM and logistic model

In Table 3, we observe little effects of the declarations of E. Macron. The coefficients that measure a variation in the likelihood that a professional belongs to one of the categories we consider are not statistically different from zero except for the last week.

We interpret this finding as evidence that the expansion of the health pass policy did not lead to a diversification of the professionals’ profiles that registered on the website. The dominant category (CAM professionals) did not gain nor lose weight. We find a similar result for the categories of professionals that likely bears the most important cost due to the policy. Thus, while there were numerous new registrations in the weeks after the announcement, the new registrants resemble the previous ones and we observe no diversification in the profiles. The result for the fourth week may somehow nuance this finding as they are statistically different from zero. A possibility would be that the announcement first re-mobilized the historical actors of the movement. Then, the movement slightly enlarged to other groups which would have affected the probability that new registrants belong to some categories. This possibility is however to consider with caution as the result is sensitive to alternative definition in the categories.Footnote 31

Is there an overall change?

Methodology

The above methodology may, however, be criticized on the ground that we focus on few (arbitrary) categories. We now consider an alternative methodology to ensure that we do not miss an overall change in the profiles. Our methodology uses cosine similarity and is implemented in several steps.Footnote 32.

To begin with, we consider the proportion of professionals in each of the 19 categories (available on the Animap.fr) at the beginning of June.Footnote 33 Those proportions describe the anti health-pass movement at its start. While we arbitrarily selected the first of June as the end of the “first wave” of registrations (and therefore use the profiles of registrants before this date as those of early registrants), using other dates has little effect on our results. Those proportions define a vector \(V_{start}\) (of dimension \(1 \times 19\)).

Then, for each subsequent day, we created a similar vector \(V_d\). It encodes the proportion of professionals in each category that registered on the website this day. Finally, for each day, we measure the cosine similarity between the vector \(V_{start}\) and \(V_{d}\) as follow:Footnote 34

\(\phi _{start,d}\) takes the value 1 when the vectors \(V_{d}\) and \(V_{start}\) are the same. That is, when the proportions of professionals registered during day d in each category are exactly similar to those that registered in April and May. As \(\phi _{start,d}\) moves toward 0, the proportions differ.

Using \(\phi _{start,d}\), we can now analyze the extent to which the new registrations on a given day resemble those at the start of the movement. In order to do so, we employ the following regression:

where all variables are similar to those used in the regression (1). However, we droped the observations before the first of June (as they are used to define \(V_{start}\)). An important remark is that the “cosine similarity” may not be defined when we observe no registration during a particular day. This creates a difficulty regarding the correction of autocorrelation in the standard errors. In the main regression, we therefore employ robust standard errors. In the appendix, we show that if we restrict the sample in order to avoid “missing days” (and therefore are able to correct for autocorrelation), we obtain similar results.

Results

The result of the analysis may be observed in Table 4, where once more we introduce the variables one at the time. In column (1), we consider the four variables that capture the effect of the announcement, in column (2) we add the fifth order polynomial. Then we add the day of week dummies in column (3) and the month fixed effects in column (4).

In this table, all the estimates for the two first weeks are positive and statistically different from zero. Thus, the expansion of the health-pass policy increased the similarity between the new and first registrants.

The positiveness of the estimates must not be thought of as a puzzling result. Our measure of similarity compares the proportion of professionals registered in each category during day d to those registered before June. As shown in Fig. 3, at the beginning of July we observe few registrations on the website. Therefore, the proportions are computed with few observations during those days. Consequently slight variations in the registrations could severely affect the proportions in a given category and therefore, impact the measure of similarity. Thus, the positive estimates should be interpreted as the fact that before the 12th, the profiles of registrants could have differed from the early registrants.Footnote 35

Figure 6 provides a way to visualize the previous finding. We plotted the measure of cosine similarity between new and early registrations. Then, we use a local polynomial of order 5 to fit the data. As it appears, the cosine similarity remains high during all the period we consider. At each date, the proportions of new registrations in each category of professionals are relatively similar to those that occurred prior June. Nevertheless, the similarity slightly decreases at the end of June (with few outliers in the data). Then, the similarity increases around the 12th of July and remains at high levels at least until mid-August.

Cosine Similarity. Source: This graph uses data from the open data of the French government. It shows the number of first doses delivered per week before and after the government extended the “Health Pass”. The two dashed lines respectively correspond to the speech of E. Macron on the 12th of July and the extension of the pass on August, 9. The data are available at: https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/donnees-relatives-aux-personnes-vaccinees-contre-la-covid-19-1/

Thus, it appears that the announcement of the expansion of the health-pass did not lead to a diversification of the registrations on Animap.fr. If any, the professionals that registered after the 12th of July resemble more to the first professionals that registered than those who did just before the 12th.

As we explained before, we believed this impacted the mobilization. The protesters on Animap.fr failed to attract new types of persons. This limited the pool of new potential participants to the collective actions. In turn, this may (partially) explain why the surge in registrations was short-termed: the movement did not attract people from other categories which limited the pool of potential registrants. Moreover, as the participants were selected from a few categories of entrepreneurs and a few industries, this may have impeded the public opinion to identify with action. On top of not participating directly, the public may have failed to sympathize with the movement.

Conclusion

In this article, we study the registrations on an anti health-pass website Animap.fr that was created in April, 2021. This website allowed entrepreneurs to claim that they would not ask for the health-pass of their clients. In particular, we analyze the dynamics of registrations following the announcements of E. Macron on the 12th of July.

We underline two main results. We find many registrations of CAM practitioners who form the largest group on the website. However, the registrants do not reduce to CAM professionals and some—such as restaurateurs or other professionals that were more directly targeted by the policy—were also present. Moreover, we find more registrations in départements that benefit from an important touristic industry. Thus, the registrations likely answered two different logics (that may have partially overlapped). Some professionals had ideological motives (e.g, the pass restricts liberty) and others had economical motives (e.g, the pass endangers businesses). This highlights the heterogeneity within the anti-pass movement and calls for a nuanced approach to such a movement. If governments rely on professionals when they build incentives schemes to increase the vaccination (e.g, the health-pass policy), they should identify professionals who will be reluctant for ideological reasons and those that are reluctant for economical reasons. Public policies seeking to help the economically motivated professionals (e.g. subventions, tax credit, etc.) or arguments that recall that alternative health policies (such as lock-down) are worse for businesses may be sufficient to obtain the support of the vast majority of such professionals. On the contrary, ideologically motivated professionals may oppose the incentives schemes whatever the policy implemented to soft their economic burden.

Second, we highlight the crucial surge in registrations after the announcement by the French Président of the generalization of the health-pass policy. This surge has some relevance for the study of social movements. It shows that events (such as the government’s announcements) are signals during which individuals revise their prior beliefs. Indeed, the expansion of the health pass hardly came as a surprise. Yet, altough it could have been anticipated, it is only after the announcement that we observe a surge in mobilization. Moreover, we suggest that despite it increases the number of participants in the mobilization, the announcement did not lead to a diversification of the profiles of the entrepreneurs who joined the action. In turn, this reveals some of the weakness of the mobilization. (a) Despite the mobilization increased, protesters were recruited only in a small part of the population. The pool of potential recruits was therefore limited. (b) The lack of diversity in the profile of registrants likely reduced the ability of the public opinion to identify (and therefore sympathize) with the anti-pass mobilization.

Our analysis may also explain a posterior the relative success of the health-pass policy. It appears that the groups of entrepreneurs that were pivotal in the enforcement of the policy (restaurateurs, bar owners, etc.) were not the main opponents to the policy: CAM professionals were. Opponents did mobilize after the announcements but the surge in mobilization ran out of steam quickly and failed to diffuse within the population.

Finally, our analysis underline the important mobilization of alternative medicine professionals in the anti-pass movements. The role of those professionals in anti-vaccination movements has been noticed for a long time (Kaufman, 1967) even if their causal influences on vaccination decision have been questioned (Bryden et al., 2018; Hornsey et al., 2020). In all cases, it is not doubtful that those professionals have been important actors in resisting the health-pass policy. It calls for future researches and for a better assessment of the externalities (either positive or negative) generated by such an industry and—if needed—to reinforce its regulation.

Notes

The health-pass is a document that attests that an individual has been vaccinated against the COVID-19, that she recovered from the disease less than six months ago, or that she was tested negative against COVID-19 less than 24, 48, or 72 hours ago. In December 2021, J. Castex, the French Prime Minister, announced the transformation of the health-pass into a vaccine-pass: only a complete vaccination scheme will provide a valid pass. Dye and Mills (2021) provides a general discussion of COVID-19 vaccination passeports.

Newspaper articles (published late August, 2021) suggest that during the summer, 179,000 controls were realized by police, leading to 1,331 fees for not complying with the health pass regulation (that is 0.74% of the controls). Penalties can range from a EUR135 fine to 6 months in prison. See France Info (31/08/2021) https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sante/maladie/coronavirus/pass-sanitaire/pass-sanitaire-179000controles-et-1331verbalisations-depuis-la-mise-en-place-du-dispositif_4754939.html.

The number is the one displayed on the website on the 21st of January 2022.

As an example: “Restaurants, commerces: les anti-passe sanitaire tentent d’agréger des lieux sans restrictions sur un site web”, Le Figaro, 21/07/2021: https://www.lefigaro.fr/conso/restaurants-commerces-sur-animap-les-anti-passe-sanitaire-tentent-d-agreger-des-lieux-sans-restrictions-20210721 or ”’Je suis prête à fermer mon restaurant !’ : des commerçants refusent d’appliquer le pass sanitaire”, France Info, 23/07/2021: https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sante/maladie/coronavirus/pass-sanitaire/je-suis-prete-a-fermer-mon-restaurant-des-commercants-refusent-d-appliquer-le-pass-sanitaire_4713225.html.

The département is a French administrative unit, sometimes compared to the U.S. county. It corresponds to the NUTS3 level of the nomenclature of territorial units for statistics in Europe.

GoogleTrend suggests that Animap.fr was rarely searched between September and December, 2021 when it experienced a short rebound. Moreover, another initiative “Animap.Job.fr” where anti-pass entrepreneurs and job seekers could post ads seem to have almost no activity. More generally, regarding the health-pass policy, polls published before the law was enacted suggested that most of the population agreed with the policy. See for instance: https://www.ladepeche.fr/2021/08/05/covid-19-les-francais-largement-favorables-au-pass-sanitaire-9716053.php.

Using rainfall as exogenous shocks on attendance, Madestam et al. (2013) also show that the number of protesters influences politicians. McAdam and Su (2002) somehow nuance the idea that number always matter. They show that congressmen and senators (in the US) discussed more about war issues after massive anti-war protests during the Vietnam war, yet this led to more pro-war votes.

Battaglini (2017) discusses the extent to which protests can be used as signals by the government.

For a model that explains protests as the consequence of (a feeling of) unfair treatment by the government, see Passarelli and Tabellini (2017).

Such a correlation is also mentioned in the review by Yaqub et al. (2014).

Our focus on CAM practitioners also echoes the finding on trust in Bargain and Aminjonov (2020). Indeed, as mentioned above, vaccine hesitancy is often related to a low level of trust in traditional medicine. In our sample, although this is not our main focus, we find qualitative evidence of a distrust in the traditional medical systems with remarks that vaccines are “genetical therapy” or are not supported by “regulatory studies.”

As already mentioned, Dye and Mills (2021) provides a general presentation of the health-pass policy and similar ones. In France, on January 2022, the “health-pass” has been transformed into a “vaccine-pass” whereby only a complete vaccination schedule will provide the pass.

See for instance: Levée progressive des restrictions sanitaires : l’examen du projet de loi par les députés s’annonce animé, Le Parisien, 10/05/2021. https://www.leparisien.fr/politique/levee-progressive-des-restrictions-sanitaires-lexamen-du-projet-de-loi-par-les-deputes-sannonce-anime-10-05-2021-SF4Y5TK6HBBCFPPLAL5IJXRVGU.php The hesitancy toward the generalization of the pass can be explained because such a policy may reinforce inequalities between citizens (for discussions, see Dye and Mills, 2021, Phelan, 2020).

Government website on the pass: https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/pass-sanitaire.

Several newspapers interviewed anti-vaccine and anti-pass people who often claim that vaccines may not be safe to use and that the pass restricts freedom. In some accounts, the overlapping between the two types of arguments may be observed. For examples of the arguments of protesters (in French): France Info, “On est empêchés de vivre” : ils expliquent pourquoi ils manifestent contre le pass sanitaire chaque samedi à Nice, 14/08/2021. https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/provence-alpes-cote-d-azur/alpes-maritimes/nice/on-est-empeches-de-vivre-ils-expliquent-pourquoi-ils-manifestent-contre-le-pass-sanitaire-chaque-samedi-a-nice-2213797.html Actu.fr, Anti-pass sanitaire : “scandale”, “piège insupportable”... Pourquoi ils manifestent, 28/08/2021, https://actu.fr/societe/coronavirus/anti-pass-sanitaire-scandale-piege-insupportable-pourquoi-ils-manifestent_44459137.html. LCI, Manifestations : pourquoi ils s’opposent au pass sanitaire, 17/07/2021, https://www.lci.fr/societe/video-manifestations-pourquoi-ils-s-opposent-au-pass-sanitaire-2191727.html.

As mentioned above, meetings were also organized in January when the health-pass became a vaccination-pass. Through the article, we focus on the events of the summer. Moreover, we always report the number of demonstrators according to the French police. Demonstrators reported higher levels of participation.

We suspect that this number includes duplicates and includes the pages that were subsequently deleted.

We found online messages written by professionals who hesitated to register on Animap.fr because they feared to be remarked by the government. See for instance the comments of the following article: https://www.francesoir.fr/politique-france/animap-le-site-des-commercants-qui-ne-demandent-ni-test-ni-vaccin

We used the package scrapeR available on the software R.

We provide descriptive statistics of those variables in the appendix B (Table 5).

The strength of the relationship should not be over-estimated as in some robustness checks the coefficient was not necessarily statistically significant. Moreover, the coefficient associated to coastal départements is not different from zero in the table.

In France, the INSEE wrote several reports on the impact of COVID-19 on tourism. See for instance: https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4995541.

The two descriptions that we have in mind are:

https://animap.fr/eintrag/assistante-maternelle-agree/ and https://animap.fr/eintrag/cabinet-d-osteopathie-2/.

We focus on the announcements and not the subsequent legislative process nor the official implementation date of the health-pass as they appear only to have modest impacts.

In the appendix, we test alternative models. In particular, we test models that include a lag of the dependent variable. As the dependent variable is an integer, we also tested counting models. Results remain qualitatively similar.

Among many examples, see for example: Les Echos, Macron dans une course de vitesse contre le variant Delta, 08/07/2021. Le Monde, Macron contraint de donner un nouveau tour de vis face au Delta, 10/07/2021. Aujourd’hui en France, Macron, retour à la case Covid, 09/07/2021. etc.

As mentioned above, we do not claim that the second category had no ideological reasons to oppose the policy. We consider that on top of ideological reasons, they had economic incentives not to apply the policy.

In the appendix, we show that we find no evidence of diversification if we use the descriptions of firms in order to decide whether professionals work in the “health” industry or if we consider only the “gastronomy” category (as restaurateurs were directly affected by the measure).

The proportion are depicted in the appendix in the Fig. 7.

In the formula below, . indicates the inner product and || the Euclidian norm.

In the appendix, we replicate this analysis using only the days where at least 10 persons registered on Animap.fr and there we observe little change in the profile of registrants through the entire period.

The standard of living measures the wealth of the household divided by a number increasing with the size of the household and the age of its members.

If \(\rho\) is the coefficient associated with the lag of the dependent variable, the long term effect associated to a coefficient \(\beta\) is: \(\frac{\beta }{1-\rho }\)

We used the glm command in Stata in order to estimate those models while considering autocorrelation concerns in the distribution.

We include keywords for “Yoga”, “Aikido”, “Shiatsu”, “Reiki” “Qi gong” “Tai chi” and “Meditation”. While they are not CAM practitioners, in the descriptions they often claimed those practises were means to improve the health of their clients.

References

Adhikari, D. B., & Lovett, J. C. (2006). Institutions and collective action: Does heterogeneity matter in community-based resource management? The Journal of Development Studies, 42(3), 426–445.

Ahn, T.-K., Ostrom, E., & Walker, J. M. (2003). Heterogeneous preferences and collective action. Public Choice, 117(3), 295–314.

Attwell, K., Ward, P. R., Meyer, S. B., Rokkas, P. J., & Leask, J. (2018). “Do-it-yourself’’: Vaccine rejection and complementary and alternative medicine (cam). Social Science and Medicine, 196, 106–114.

Bargain, O., & Aminjonov, U. (2020). Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of Covid-19. Journal of Public Economics, 192, 104316.

Battaglini, M. (2017). Public protests and policy making. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1), 485–549.

Bean, S. J. (2011). Emerging and continuing trends in vaccine opposition website content. Vaccine, 29(10), 1874–1880.

Blondel, S., Langot, F., Mueller, J., and Sicsic, J. (2021). Preferences and Covid-19 vaccination intentions. IZA DP No. 14823.

Blume, S. (2006). Anti-vaccination movements and their interpretations. Social Science and Medicine, 62(3), 628–642.

Bryden, G. M., Browne, M., Rockloff, M., & Unsworth, C. (2018). Anti-vaccination and pro-cam attitudes both reflect magical beliefs about health. Vaccine, 36(9), 1227–1234.

Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2022). Post-Covid-19 recovery of island tourism using a smart tourism destination framework. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 23, 100689.

Chow, M. Y. K., Danchin, M., Willaby, H. W., Pemberton, S., & Leask, J. (2017). Parental attitudes, beliefs, behaviours and concerns towards childhood vaccinations in Australia: A national online survey. Australian Family Physician, 46(3), 145–151.

Deml, M. J., Notter, J., Kliem, P., Buhl, A., Huber, B. M., Pfeiffer, C., Burton-Jeangros, C., & Tarr, P. E. (2019). “We treat humans, not herds!’’: A qualitative study of complementary and alternative medicine (cam) providers’ individualized approaches to vaccination in switzerland. Social Science and Medicine, 240, 112556.

Dye, C., & Mills, M. C. (2021). Covid-19 vaccination passports. Science, 371(6535), 1184.

Gao, J., Jun, B., Pentland, A. S., Zhou, T., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2021). Spillovers across industries and regions in China’s regional economic diversification. Regional Studies, 55(7), 1311–1326.

Gavrilets, S. (2015). Collective action problem in heterogeneous groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1683), 20150016.

Heckathorn, D. D. (1993). Collective action and group heterogeneity: Voluntary provision versus selective incentives. American Sociological Review, pages 329–350.

Hoffman, B. L., Felter, E. M., Chu, K.-H., Shensa, A., Hermann, C., Wolynn, T., Williams, D., & Primack, B. A. (2019). It’ s not all about autism: The emerging landscape of anti-vaccination sentiment on Facebook. Vaccine, 37(16), 2216–2223.

Hornsey, M. J., Lobera, J., & Díaz-Catalán, C. (2020). Vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with distrust of conventional medicine, and only weakly associated with trust in alternative medicine. Social Science and Medicine, 255, 113019.

Kaufman, M. (1967). The American anti-vaccinationists and their arguments. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 41(5), 463–478.

Koffi, M. (2021). Innovative ideas and gender inequality. University of Waterloo Working Paper Series, 35.

Kowalewski, M. (2021). Street protests in times of Covid-19: Adjusting tactics and marching ‘as usual’. Social Movement Studies, 20(6), 758–765.

Li, S., Wang, Y., Filieri, R., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Eliciting positive emotion through strategic responses to Covid-19 crisis: Evidence from the tourism sector. Tourism Management, 90, 104485.

Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2013). Do political protests matter? evidence from the tea party movement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1633–1685.

Martin, S., & Vanderslott, S. (2022). “Any idea how fast ‘it’s just a mask!’can turn into ‘it’s just a vaccine!’’’: From mask mandates to vaccine mandates during the covid-19 pandemic. Vaccine, 40(51), 7488–7499.

McAdam, D., & Su, Y. (2002). The war at home: Antiwar protests and congressional voting, 1965 to 1973. American sociological review, pages 696–721.

Nugier, A., Limousi, F., & Lydié, N. (2018). Vaccine criticism: Presence and arguments on French-speaking websites. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses, 48(1), 37–43.

Oliu-Barton, M., Pradelski, B. S. R., Woloszko, N., Guetta-Jeanrenaud, L., Aghion, P., Artus, P., Fontanet, A., Martin, P., & Wolff, G. B. (2022). The effect of COVID certificates on vaccine uptake, health outcomes, and the economy. Nature Communications, 13(1), 3942.

Olson, M. (1971). The Logic of Collective Action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

Passarelli, F., & Tabellini, G. (2017). Emotions and political unrest. Journal of Political Economy, 125(3), 903–946.

Phelan, A. L. (2020). Covid-19 immunity passports and vaccination certificates: Scientific, equitable, and legal challenges. The Lancet, 395(10237), 1595–1598.

Pressman, J., & Choi-Fitzpatrick, A. (2021). Covid19 and protest repertoires in the united states: An initial description of limited change. Social Movement Studies, 20(6), 766–773.

Sangnier, M., & Zylberberg, Y. (2017). Protests and trust in the state: Evidence from African countries. Journal of Public Economics, 152, 55–67.

Tilly, C. (2004). Social Movements, 1768–2004. Routledge.

Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. G. (2015). Contentious politics. Oxford University Press.

Varughese, G., & Ostrom, E. (2001). The contested role of heterogeneity in collective action: Some evidence from community forestry in Nepal. World Development, 29(5), 747–765.

Ward, J. K., Gauna, F., Gagneux-Brunon, A., Botelho-Nevers, E., Cracowski, J.-L., Khouri, C., Launay, O., Verger, P., & Peretti-Watel, P. (2022). The French health pass holds lessons for mandatory Covid-19 vaccination. Nature Medicine, 28(2), 232–235.

Wouters, R. (2018). The persuasive power of protest. How protest wins public support. Social Forces, 98(1), 403–426.

Wouters, R., & Walgrave, S. (2017). Demonstrating power: How protest persuades political representatives. American Sociological Review, 82(2), 361–383.

Yaqub, O., Castle-Clarke, S., Sevdalis, N., & Chataway, J. (2014). Attitudes to vaccination: A critical review. Social Science and Medicine, 112, 1–11.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marcos Vera-Hernandez and an anonymous referee for helpful comments. They help us to improve our manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

No human subjects were recruited or analyzed in this study. All the data were obtained from online and publicly available sources. As mentioned above, we use the package ScrapeR in order to automatically extract information from websites.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflict of interest regarding the subject of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

A Descriptive statistics at the département level and regressions at the département level

In the Table 5, we provide descriptive statistics on the number of registrations by département (and the total number of registrations). We also provide descriptive statistics on the variable used in Sect. 4.3 where we study the geographic variation in the mobilization. In particular, we use the census population of départements (in 2018), their unemployment rate during the first trimester of 2019 (before the pandemic started) and the median “standard of living” of households in 2017 (as a measure of the wealth of their population).Footnote 36 Finally, we consider the number of nights that people spent in touristic facilities in the département in 2019. This variable provides our primary information regarding the importance of the touristic industry in the département.

B Descriptive statistics on the first wave of registration

In the main text, we analyze whether the announcement of the expansion of the health-pass had an impact on registrations on Animap.fr and whether this affected the diversity of profiles of professionals. Thus, we compare the profiles of persons that registered after the 12th of July to those that registered before.

Here, we provide descriptive statistics on the profile of those that registered on the website before the first of June; based on Fig. 3, we arbitrary selected this date in order to delimitate the first wave of registrations but we have checked beforehand that taking other dates into account does not significantly affect the results.

On this date, we counted 3,078 different pages. 33.82% of them have written a description, although it is often a basic explanation of what the company does. More interestingly, we used the informed category of professionals and plotted them in Fig. 7. This reveals the high percentage of professionals working in the health industry. Two items should be noted, however: (a) Nearly all professionals are CAM practitioners (naturopathy, energy healing, Chinese medicine, etc.), (b) the percentage (22%) is underestimated because many CAM practitioners selected other categories (such as “services” or “other”).

At least 21% of the professionals who (i) wrote a description and (ii) did not select the “health and medicine” category seem to be CAM practitioners. To obtain this figure, we simply detected keywords (such as naturopath, osteopath, etc.) in the descriptions. This percentage increases further if we also count professionals such as yoga teachers who—although not providing health care—often suggest that they could improve the health of their clients.

C The effect of the announcements on the number of registrants: supplimentary tables

In the main text, when we estimate the effect of the announcement of E. Macron, we use the Newey-West standard errors in order to control for the autocorrelation in our data. In Table 6 we re-estimate the above model with several modifications: (a) we allow for a higher order of autocorrelation in the standard errors (column 1) or (b) assume no autocorrelation (column 2). Then, (c) we include the lag term of the dependent variable (column 2, 3 and 4). In the columns that include a lag term, the results remain coherent with our previous estimates. Indeed, the instantaneous effect of the announcement consists of only 75 additional registrations for the first week and 22 for the second week. However, as the model allows for dynamic effect (through the lag term), the long term effects are respectively 183 and 56. Those effects are close from the previous non-dynamic estimates.Footnote 37

In the main text, we use simple linear regression models in order to estimate the effect of the announcement of the expansion of the health-pass on the number of registrants on Animap.fr. While this has the advantage of simplicity, a potential concern deals with the nature of the data that takes value in the set of positive integers. This can be observed in the Table 8.

In order to insure the robustness of our results, we therefore re-estimate the model on the effect of the registrations using both Poisson and Negative binomial counting models. The results of such an exercise may be observed in Table 7.Footnote 38

The table also suggests a strong effect of the announcements but that the effect strongly decreases over-time. Here we obtain a statistically significant effect for the third and fourth weeks. As the marginal effects are not easily readable through the table, we also predicted the number of registrations using the estimates. Then, we computed the average predicted number of registrations during the week before the announcement and then in the weeks after the announcements of E. Macron. The model (2) predicts 170.4 additional registrations during the first week after the announcements with respect to the pre-announcement period, 72.4 during the second week, 27.8 during the third week and 25.2 during the fourth week. Model (4) predicts respectively 167.8, 72.4, 27 and 25.3 extra-registrations during the four weeks. Those numbers are comparable to those of Table 2, although once more, the effect on the third and fourth weeks are slightly more pronounced.

Announcements and the diversity of entrepreneurs: supplementary tables

In the main text, we measure whether the probabilities to find a professional of the health industry or a professional from industries that may have been targeted by the policy vary after the announcements of E. Macron. The first category is not directly targeted by the policy but—as it contains CAM—is over-represented in the movement. The second category was directly targeted by the health-pass.

In Table 8 we repeated the same analysis but use alternative ways to define the type of professionals we analyze. In columns (1) and (2), we use the descriptions of the firms on Animap.fr. We detectected 37 keywords related to health, CAM or close activities.Footnote 39 We use the presence of those words in the description in order to infer they were opposed to the pass for ideological motives.

Then, in column (3) and (4) we consider only restaurant owners. Those professionals had to check the health pass of their clients and therefore were targeted by the policy.

As in the main text, we observe little changes in the probability to find professionals in those categories after the speech of E. Macron.

In the main text, when we measure the cosine similarity between early registrants and the others, we observe an increase in (cosine) similarity after the 12th of July. We explained that this was due to the very few registrations observed in the weeks before the 12th of July.

Here, we replicate the analysis using only the days where we observe a minimum of 10 registrations. This is done in Table 9. In this table, most of the estimates are not statistically different from zero. This once more implies that the announcement of E. Macron did not lead to a diversification in the profile of protesters.

Similarly, in the main text, we explain that (due to the impossibility to compute the cosine similarity when we observe no registration), the temporal nature of the data might be complex to accommodate. In particular, we cannot control for autocorrelation in the standard errors. In Table 10, we employ several method to take this issue into account. In column (1) and (2) we add a lag of the dependent variable (in column (2), we further restrict the sample to days with at least 9 observations). A re-insuring fact is that the lag variable is not statistically significant. Then, in column (3) and (4), we restrict the sample to the series of days (between the 28 of June and the 25 of August) where the serie is complete. This does not affect the findings.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lévêque, C., Megzari, H. Intensification or diversification: responses by anti health-pass entrepreneurs to French government announcements. Int J Health Econ Manag. 23, 553–583 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-023-09355-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-023-09355-y